Summary

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 ("SDWA"), proposed by Senator Warren Magnuson (D-WA), sought to safeguard public water resources from any contamination by enacting "programs that establish standards and treatment requirements for public water supplies, finance drinking water infrastructure projects, promote water system compliance, and control the underground injection of fluids to protect underground sources of drinking water (Tiemann 2017, 1)." Under the oversight of the Environmental Protection Agency, these water-quality standards apply to all public tap water sources. These ground-breaking standards sought to address the lack of decisive federal regulations of contaminant levels in the water supply.

The measure's consideration and passage came during a period of heavy concern for environmental issues and consumer safety. It passed the Senate during the 92nd Congress, the Safe Drinking Water Act failed to pass the House due to disagreements over this bill’s expansion of the Environmental Protection Agency. Opponents felt the measure went too far in empowering the federal government at the expense of the states. One of the strongest forces on the opposition was President Richard Nixon. In fact, during Nixon's address to Congress, he declared that while "we must take new steps to protect the purity of our water, the federal government’s role, however, should not be that of direct regulation but rather that of stimulating state and local government's" ability to monitor and establish new water standards.[1] After the resignation of President Nixon in the Summer of 1974, the route to this bill’s passage become easier.

Much of the conflict over the bill in the 93rd Congress occurred in the House and Senate committees. On the House side, there was some concern the proposal would be blocked by the House Rules Committee. Once again, the conflict centered on the same points Nixon expressed regarding state's rights and the balance of federal power. The measure passed the Senate by voice vote early in the first session. It passed the House the following year in the second session on a roll call vote of 296-84.[2] President Ford signed and approved the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 on December 16, 1974. He called it a "strong bill" and noted that "states [and not the EPA] will have the primary responsibility of enforcing the standards."[3]

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 was listed as a landmark act by Stathis (2003, 2014) and was ranked as the 38th most influential enactment of the 93rd Congress by Clinton and Lapinski (2006).

Background

The 93rd Congress convened from January 3, 1973 to January 3, 1975 during the last few months of the Nixon presidency and the beginning of the Ford presidency. This specific Congress was the first, and only, body to experience two presidents and three vice presidents.[4] After the fallout from the tumultuous Nixon presidency, the Democratic Party held both chambers of Congress by a margin of 54-44 in the Senate[5] and 243-192 in the House of Representatives.[6] This Congress was most known for its efforts to create more governmental transparency through the Freedom of Information Act, to reestablish the powers of Congress at the expense of the Executive Branch[7] and its attempted impeachment of President Nixon.

The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 was enacted during the second session of the 93rd Congress. Though most of the work to formulate a bill to protect and enforce public water standards began years earlier, serious consideration and urgency to pass the bill coalesced in the second session of the 93rd Congress. After gaining momentum for action through increased advocacy from Ralph Nader and the EPA and grassroots demand for change, the 93rd Congress began meaningful work on drafting the Safe Drinking Water bill.

The EPA was established in 1970 during a wave of environmental and consumer activism. This activism was largely based on a wide number of studies demonstrating the negative impact of pollution on health. And while Congress had appropriated a substantial amount of funds for water pollution control, comparatively little targeted drinking water quality. The Senate Commerce Committee report on S 3994 during the 92nd Congress noted: "Federal funding for water pollution control was $1-billion in fiscal 1972 while federal expenditures for drinking water supply programs reached $4.3-million in fiscal 1972. States spend an additional $10-million on drinking water programs according to the committee (CQ Almanac 1972, 28th Edition)." This disappointing discrepancy in the amount of money spent by state governments and the substandard results produced without the EPA’s substantial, federal oversight proved the necessity of some state-accountability system.

By this point a number of studies had highlighted problems with contaminated drinking water. These studies linked, among other things, outbreaks of disease and poisoning to drinking water, reported at least twelve urban areas with high levels of arsenic in their water, found links between high levels of cadmium in drinking water and heart disease, and demonstrated high levels of mercury in Americans drinking water.[8] Additional reports suggesting contaminated drinking water may be causing cancer spurred sales of bottled water.[9] Consumer advocate Ralph Nader argued that "half of all Americans drink water below federal standards."[10] Furthermore, with regards to the states' request for more control over public water systems and the enforcing the standards instead of the EPA, Nader declared that this concession of allowing the states to exclude EPA oversight made the public "guinea pigs in this environmental version of Russian Roulette (CQ Almanac, 1973, 29th Edition)." This led Magnuson to introduce S 3994 in the 92nd Congress. While that measure passed the Senate by voice vote, no House bills were reported out of committee.

Initial Senate Consideration (June 22, 1973)

On January 18, 1973, Magnuson, the Chairman of the Senate Committee of Commerce, introduced S 433, the Safe Drinking Water Act to the Senate on behalf of himself and 23 other Senators. In a brief speech, he advocated for its necessity for sanitary conditions and potable tap water for all people. He observed that:

"The Environmental Protection Agency has estimated that the States should be spending approximately three times the money they now spend to do a proper job of administering state drinking water programs. And the outlook is not good. As new demands are being placed on State governments to devote resources to water pollution clean-up and other programs, there is increasing pressure to do so at the expense of drinking water programs. While water pollution cleanup is an obvious first order necessity, it is unfortunate that similar priorities have not been attached to State drinking water supply programs (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, January 18, 1973, 1384)."

In addition, Magnuson emphasized the unhealthy state that public water systems nationwide were in before the bills introduction by providing shocking facts about water systems nationwide. For instance, Magnuson stated that "ninety percent [of the drinking water systems] failed to meet the biological surveillance criteria of the current drinking water standards for interstate carriers" (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, January 18, 1973, 1384). The lack of a sufficient oversight to monitor these conditions and federal provisions to address the lack of funding led to Magnuson's inclusion of the EPA as a regulatory agency and director of federal funds for failing water systems.

The Senate then referred the bill onto the Senate Committee on Commerce without contention.

While in the Senate Committee on Commerce, Magnuson facilitated a discussion between Mr. Henry Eschwege, Director of Resources and Economic Development Division of the General Accounting Office, Mr. Phillip Charam, Deputy Director of the Energy and Environmental Programs, and Mr. Edward Densmore, Assistant Director of the Accounting Office’s division for coordinating with the EPA. These individuals were summoned by Magnuson to explain their findings of an EPA study on the overall state of national public water systems to the Subcommittee on the Environment of the Committee on Commerce. This report detailed the poor state of water systems nationwide; thus, further exemplifying the necessity of this bill in providing substantially safe water for all residents of the United States (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress: Senate Committee on Commerce Report, July 10, 1973, 63).

After hearing these findings, the bill was reported to the general body of the Committee on Commerce for consideration and debate. The Committee on Commerce established two minor changes to Magnuson’s original S 433 which included the following two changes: a study on the contamination of groundwater and the establishment of a program allocating one percent of federal funds allotted for state water programs (CQ Almanac 1973, 29th Edition). S 433 was reported by the Committee on Commerce on June 20, 1973.

On June 22, 1973, the Senate Majority Leader, Senator Mike Mansfield (D-MT) asked for, and received, unanimous consent that the Senate proceed to S 433. This motion was followed by two speeches in support of the bill by Magnuson and co-sponsor, Senator Phil Hart (D-MI). Magnuson argued "[i]t is seldom that a bill of this import comes before the Senate." Hart noted that studies on clean water have "jolt[ed] us all out of a certain apathy that exists with respect to drinking water." He added that the bill "has near universal support (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, June 22, 1973, 20813.)" The bill then passed the Senate via voice vote.[11]

Initial House Consideration (November 19, 1974)

Rep. Paul Rogers (D-FL) introduced a companion bill (HR 13002) entitled the National Water Hygiene Act, on February 21, 1974.[12] The bill was referred to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Nonetheless, this bill faced substantial opposition in the House. Rogers' bill sought to address the issue of federal standards for public water sources by recognizing the Public Health Service Act which protected the public from any "public health concerns," such as the spreading of diseases via archaic public water standards.[13] For instance, many oil executives lobbied heavily against the HR 13002 due to the waste injection contingency of this bill.[14] For instance, this opposition to Roger's National Water Hygiene Act was further displayed in a letter by Roy Ash, the previous Office of Management and Budget Director, to House leaders stating the following: "The current bill will result in federal regulation of every aspect of over 400,000 local water treatment plants and is another step in reducing state and local governments to be near caretakers of the Washington bureaucracy (Hoyt 1974)."

The bill was met with additional hostility in committee for its alleged infringement of states’ rights by enabling the EPA to have oversight of large-scale public water systems.[15] For example, Rep. James Hastings (R-NY), asserted that under the current bill provisions "every time we open up a water tap in every house in the United States of America, we will find an EPA inspector coming out of that water tap" (CQ Almanac 1974, 30th Edition). Other concerns included claims of seemingly unwarranted governmental intervention in state-related matters, such as providing adequate potable tap water without casting the undue monetary burden of the EPA's demands. After much debate, the Committee agreed to "give the EPA the back-up authority of a state abuses its discretion in carrying out its primary responsibility" when enforcing the established standards; nevertheless, the committee organized "strict requirements for use of the federal enforcement power" to address the Committee's concerns of infringing on a states' reserved powers (CQ Almanac 1974, 30th Edition). The bill was then voted out of committee on August 15, 1974 via voice vote.[16]

One of the major differences between Rogers' National Water Hygiene Act and Magnuson's Safe Drinking Water Act differed in their approach to the requisites for EPA intervention and the primary standards to be established for intervention. For instance, HR 13002 required any EPA intervention to be based upon a contamination of a water system alone and the enforcement of these newly established standards be after a period of "180 days of [the bill's] enactment...and a report on national standards prepared by the National Science Academy, due within two years of enactment" (CQ Almanac 1974, 30th Edition). This three-year time frame differed from Magnuson's bill which provided for a speedier implementation of these standards.

HR 13002 was met with additional resistance in the House Rules Committee, which was chaired by Rep. Ray Madden (D-IN). Some on the committee sought to delay the bill once again until possibly the next session.[17] This was met with derision by several newspaper outlets. For example, the Washington Post who claimed that if the Rules Committee does not rethink its decision, "it [would be] hard to imagine that anyone in Congress will want to face voters in November and report that he didn’t do anything about getting clean tap water for its citizens."[18] Eventually, a rule (Hres 1423) for HR 13002 was granted and reported out by the Rules Committee.

The House Rules Committee reported Hres 1423 to the floor on November 19th, 1974. Hres 1423 was an open rule that provided for amendments under the five-minute rule.[19] During consideration of the rule, debate was largely confined to the substance of the bill.[20] Conservatives largely spoke against centralized control of the issue. For example, Rep. Delbert Latta (R-OH) argued the legislation would make it difficult for communities to have access to water if the EPA shut down their water treatment facilities for not meeting federal standards.[21] In contrast, Rogers argued the bill was "significant for America" and "would give control to the states, to the local areas, not to the EPA (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 19, 1974, 36368)." Both the previous question motion on the rule and the rule itself were adopted by voice vote.

Debate on the bill largely focused on impinging on state power and forcing the federal government to bear the brunt of the costs. Conservative opponents complained that the bill’s popularity was largely due to marketing and not the underlying substance. For example, Latta argued that the House should do away with bill titles as no member could possibly "vote against a piece of legislation entitled 'The Safe Drinking Water Act' (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 19, 1974, 36367)." Rep. Philip Crane (R-IL) announced that to protect state rights "[there] are those of us who at time must vote against God, motherhood and apple pie."[22]

House deliberation on balancing state and federal powers eventually lead to the consideration of controversial amendments that would slowed the SDWA's passage dramatically. For instance, Rep. Phillip Ruppe (R-MI) proposed a contentious amendment limiting the amount of toxic waste that could be dumped into bodies of public water. In particular, Ruppe's amendment challenged practices of Reserve Mining company who consistently dumped thousands of gallons of toxic, asbestos-ridden waste into Lake Superior.[23] Ultimately, this amendment failed via voice vote. In total, the House considered nine amendments, seven of which were adopted. All nine amendments were dispensed with via unrecorded voice vote.

The House eventually passed HR 13002 as amended 296-84 on November 11.[24] The vote was bipartisan with 116 Republicans joining 180 Democrats in supporting the measure while 33 mostly Southern Democrats and 51 Republicans voted no. The House then inserted the text of HR 13002 into the Senate passed S 433.

Secondary Senate Consideration (November 26, 1974)

Senate and House leaders worked quickly to resolve differences between the two drafts. On November 26, Senator Hart moved to concur in the House amendment to the Senate bill with an amendment. He argued that the House-passed bill reflected a great deal of "thought and effort" and added that "the changes necessary to the House bill to bring it closer to conformity with the Senate bill are not extensive" a formal conference was not necessary. Moving quickly, he argued, "serve[d] the very useful purpose of giving the Congress an opportunity to override a Presidential veto, should that occur (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 26, 1974, 37590)."

Senate debate over Hart's motion was brief. Of primary concern to some senators was the House bill dropped a provision that ensured no state would receive less than one percent of the total grant money available. Hart's amendment included this provision, which was designed to satisfy these small-state senators. Among them, was Senator Norris Cotton (R-NH), the ranking member on the Committee on Commerce.

Cotton expressed his appreciation for Hart's amendment. He noted that some of the changes may lead to a veto, but he noted he was "not going to hold up consideration of our labor-HEW conference report" by arguing over them. He also expressed his understanding that Hart wanted to avoid a potentially fatal pocket-veto. Cotton concluded his support for the bill and Hart’s motion, claiming "if one votes against safe drinking water, it is like voting against home and mother (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 26, 1974, 37594)." Hart’s motion to concur in the House amendment with an amendment was agreed to by voice vote.

Secondary House Consideration (December 3, 1974)

Floor consideration of the Senate's amendment occurred on December 3, 1974. Rep. Harley Staggers (D-WV) asked for and received unanimous consent to take the bill from the table and offer a motion to concur in the Senate amendment to the House amendment to the bill. House consideration was also brief. Much of the floor discussion revolved around the Senate amendment prescribing the jurisdiction of federal courts when filing suit against any non-compliant public water systems. The amendment, which Staggers referred to as the "only significant [Senate amendment]" would ensure no suits could be brought against public water systems for 27 months after the law was enacted (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, December 3, 1974, 37874).

After Staggers finished explaining the Senate amendment, two Texas Democrats (Reps. Abraham Kazan and Ovie Fisher) gave brief statements outlining their continued opposition to the bill. Nonetheless, the House concurred in the Senate amendment to the House amendment to S 433 by voice vote.

Aftermath

President Ford eventually signed the SDWA of 1974 into law on December 16, 1974 (93 PL 523) despite opposing it on several grounds. The law was amended in later congresses and expanded to further provide public water consumption standards. This act formed a solid accountability system and set standards and procedures for public water systems nationwide.

Decades after the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974, the issue of having potable, adequate public water is still debated with regards to the seemingly antiquated infrastructure of cities across the United States. While the Safe Drinking Water Act laid the foundation for better regulation of water systems, the EPA's oversight has been recently undermined by the water crisis in the Flint, Michigan water system.

Overview

Session/Sessions: 1-2

Statute No: 88 Stat. 1660-1694

Public Law No: 93-523

Eid: 930523

Bill: S 433

Sponsor: Senator Warren G. Magnuson (D-WA)

House Committees: Interstate and Foreign Commerce

Senate Committees: Commerce

Companion Bill: HR 13002

Related Bills: 93 HR 5368; 93 HR 1059; 93 HR 5395; 93 HR 9726; 93 HR 10955; 93 S 2846

House Rules: Hres 1423

Past Bills: 92 HR 1093; 92 HR 437; 92 HR 14899; 92 HR 3994;

Introduced Date- Law Date: January 28, 1973- December 16, 1974

House Floor Days: 2

Senate Floor Days: 2

Roll Call Votes: 1

Tags: environment; ping-pong

As with most older cities predating the SDWA of 1974, the water systems of older communities and towns still have the "lead soldering" to seal pipes and other water system infrastructure.[25] Since the replacement of these pipes and can be costly and expensive, this outdated infrastructure generally remains intact. In an attempt to save the impoverished city money, the city’s local city council authorized the city to tap into the Flint River water source. During the switch, as citizens began to report more cases of foul-smelling and discolored water coming from their taps, studies found "fecal coliform bacteria" in the water and an immediate city warning was issued.[26]

This issue only foreshadowed further studies into Flint's public water infrastructure that led to a confirmation of unsafe levels of lead in the water. In response to this impending crisis, the EPA was dispatched to evaluate the situation only to find that the levels of lead found were "as high as 13,200 parts per billion, which is over 2.5 times the classification of toxic lead waste and 880 times the action level of 15 ppb established by the EPA" (Roy 2015, 2).

This example of the Flint water systems is a testament to the antiquated infrastructure that plagues communities, specifically smaller communities, across the nation. While the Safe Drinking Water Act once laid the foundation for water systems nationwide with regards to protecting the health of all citizens, some argue that more spending on infrastructure nationwide is critical to enabling the use of the SDWA in the current times.

Citations

Clinton, Joshua and John Lapinski. 2006. "Measuring Legislative Accomplishment, 1877-1994," American Journal of Political Science 50(1): 232-249.

CQ Almanac. 1974. "Safe Drinking Water."

Monty, Hoyt. 1974. "Safe Drinking Bill Heads for Decision," The Christian Science Monitor, October 7.

Poole, Keith and Howard Rosenthal. 1997. Congress: A Political-Economic History of Roll Call Voting. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Roy, Siddhartha. 2015. "Hazardous Waste-Levels of Lead Found in a Flint Household's Water." Flint Water Study Updates, September. flintwaterstudy.org/2015/08/hazardous-waste-levels-of-lead-found-in-a-flint-households-water/

Stathis, Stephen W. 2003. Landmark Legislation 1774-2002: Major U.S. Acts and Treaties. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press.

Stathis, Stephen W. 2014. Landmark Legislation, 1774-2012: Major U.S. Acts and Treaties, 2nd Edition. Washington: CQ Press

Tiemann, Mary. 2017. "Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements." Congressional Research Service, March 1. fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL31243.pdf

Footnotes

[1] "Excerpts from Nixon’s Message to Congress," The Atlanta Constitution, September 11, 1973.

[2] Voteview 93rd House RC #1006 (Poole and Rosenthal 1997). https://voteview.com/rollcall/RH0931006

[3] "Ford Signs Safe Drinking Water Bill," Washington Post, December 18, 1974.

[4] See http://history.house.gov/Congressional-Overview/Profiles/93rd/

[5] See https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm

[6] See http://history.house.gov/Congressional-Overview/Profiles/93rd/

[7] See e.g. the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act (93 PL 344) and the War Powers Resolution (93 PL 148).

[8] See e.g. Hall, John. 1970. "Mercury Disaster is Feared." The Atlanta Constitution, July 30; Hill, Gladwin. 1974. "Bill for Pure Water Standards Facing New Hurdles in Congress," Washington Post, October 6; Stuart, Peter C. 1972. "A Drink of Water-But is it Fit to Drink?" Christian Science Monitor, April 21; Cherry, Rona and Laurence Cherry. 1974. "What's in the Water We Drink: Strange as it Seems, the Best Drinking Water is in New York City." New York Times, December 8.

[9] Feaver, Douglas. 1974. "Cancer Talk Spurs Bottled Water Sales," Washington Post, November 14.

[10] Stuart, Peter C. 1972. "A Drink of Water-But is it Fit to Drink?" Christian Science Monitor, April 21.

[11] See "Water Bill Approved by Senate," Washington Post, June 23, 1973.

[12] The chairman of the subcommittee on Health and the Environment, Rogers earned the nickname “Mr. Health” because of his sponsorship and advocacy of bills like the National Cancer Act of 1971, the Health Maintenance Organization Act and the Clean Air Act (Hevesi, Dennis. 2008. "Paul G. Rogers, 'Mr. Health' in Congress, Is Dead at 87." New York Times, October 15.)

[13] See http://www.astho.org/Programs/Preparedness/Public-Health-Emergency-Law/Emergency-Authority-and-Immunity-Toolkit/Public-Health-Service-Act,-Section-319-Fact-Sheet/

[14] Monty, Hoyt. "Safe Drinking Bill Heads for Decision," Christian Science Monitor, October 7, 1974.

[15] As defined by the record, a public water system is a conglomeration of 15 or more service connections.

[16] https://www.congress.gov/bill/93rd-congress/house-bill/13002/actions

[17] Hill, Gladwin. 1974. "Bill for Pure Water Standards Facing New Hurdles in Congress," Washington Post, October 6.

[18] Washington, Mary Russell. 1974. "House Passes Bill on Safe Drinking-Water Standards," Washington Post, November 20.

[19] An open rule enables representatives on the House floor to propose germane amendments.

[20] The text of Hres 1423:

H. Res. 1423

Resolved, That upon the adoption of this resolution it shall be In order to move that the House resolve itself into the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union for the consideration of the bill (H.R. 13002) to amend the Public Health Service Act to assure that the public is provided with safe drinking water, and for other purposes. After general debate, which shall be confined to the bill and shall continue not .to exceed one hour, to be equally divided and controlled by the chairman and ranking minority member of the Committee on Inter- state and Foreign Commerce, the bill shall be read for amendment under the five-minute rule. It shall be in order to consider the amendment in the nature of a substitute recommended by the Committee on Inter- state and Foreign Commerce now printed in the bill as an original bill for the purpose of amendment under the five-minute rule. It shall also be in order to consider the text of the bill H.R. 16760 if offered as an amendment in the nature of a substitute for the said committee amendment. At the conclusion of the consideration of H.R. 13002 for amendment, the Committee shall rise and report the bill to the House with such amendments as may have been adopted, and any Member may demand a separate vote in the House on any amendment adopted in the Committee of the Whole to the bill or to the committee amendment in the nature of a substitute. The previous question shall be considered as ordered on the bill and amendments thereto to final passage without intervening motion except one motion to recommit with or without instructions. After the passage of H.R. 13002, the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce shall be discharged from the further consideration of the bill S. 433, and it shall then be in order in the House to move to strike out all after the enacting clause of the said Senate bill and insert in lieu thereof the provisions contained in H.R. 13002 as passed by the House (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 19, 1974, 36366).

[21] Latta first noted that "this is an extremely important piece of legislation. I think the Members in this Chamber should take note of the legislation to be considered, if this rule is adopted, as it will affect the water systems of every community and every city in this Nation. That is important legislation, and it Is nationwide in scope (Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, November 19, 1974, 36367)."

[22] Lyons, Richard D. 1974. "Water Purity Bill is Voted on by House." New York Times, November 20.

[23] Washington, Mary Russell. 1974. "House Passes Bill on Safe Drinking-Water Standards," Washington Post, November 20.

[24] See Voteview 93rd House RC #1006 (Poole and Rosenthal 1997). https://voteview.com/rollcall/RH0931006

[25] Smithhisler, Nora. 2018. "The Safe Drinking Water Act and Flint, Michigan: How We Can Update Our Standards for Safe Drinking Water." Cornell Policy Review, May 31. http://www.cornellpolicyreview.com/sdwa-flint-michigan/.

[26] Emery, Amanda. 2015. "Flint Issues Boil Water Notice for Portion of West Side of City," Mlive, January 17. https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/index.ssf/2014/08/flint_issues_boil_water_notice.html.

![Above: The sponsor of the Safe Drinking Water Act, Senator Warren Magnuson (D-WA), argued that "ninety percent [of the drinking water systems] failed to meet the biological surveillance criteria of the current drinking water standards for interstate…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ae8a979e17ba33451e0589f/1542022613583-KW6A9DGUOHZ2XN61X2BX/Magnuson.jpg)

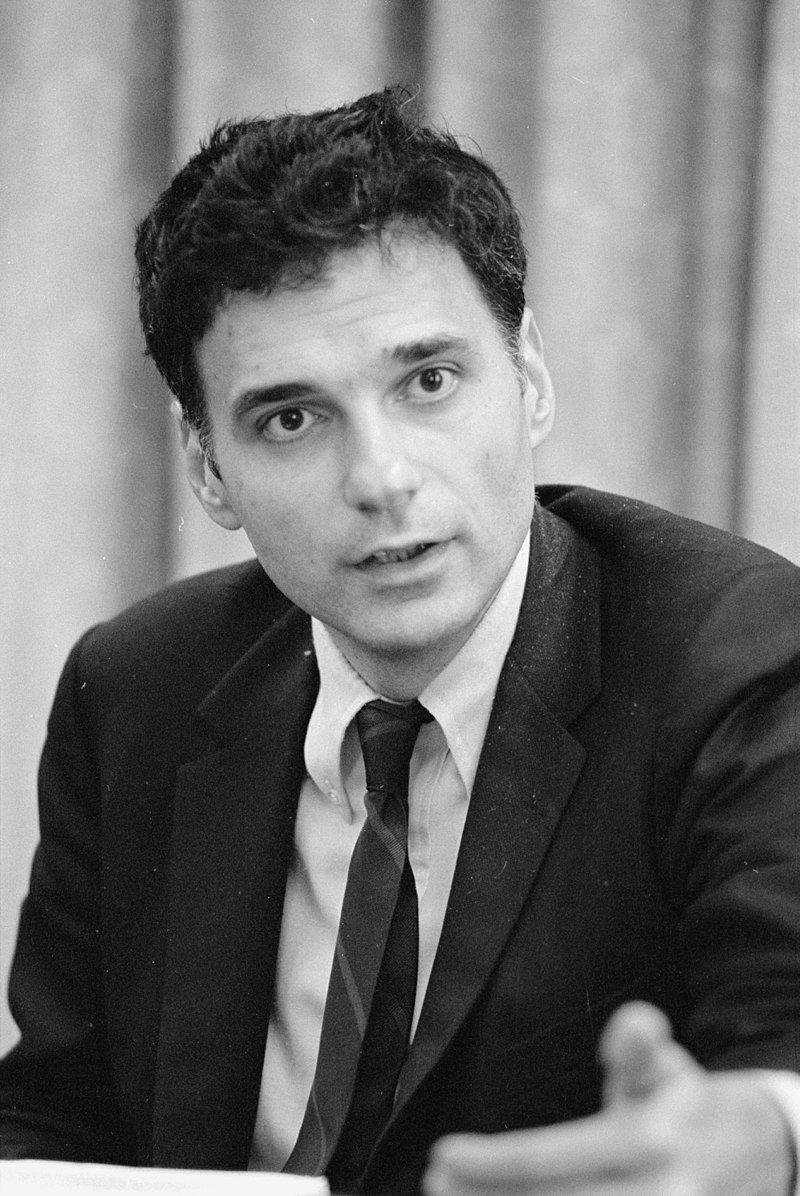

![Above: To protect states rights, Rep. Phil Crane (R-IL) argued "[there] are those of us who at time must vote against God, motherhood and apple pie."](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ae8a979e17ba33451e0589f/1552576046022-O5ZMJ23E4MXLQUL19P77/PhilCrane.jpg)